“Putting the cart before the horse” is a French expression that illustrates an absurd situation where you wait for the consequences of an event… that never happened. For example: receiving a meal at home without ever having ordered it, or already imagining yourself behind the wheel of a new car without even checking your credit rating to see if you can afford it.

The obvious is not always as simple as it seems. For decades, the industry operated on a firm belief: to know if a product will sell, you first have to produce it. Automobiles, household appliances, fashion—everything was based on this linear logic: design, production, then marketing.

When Agile Product Management methodologies emerged, they challenged this certainty. Their message of “test quickly to fail quickly” was often misunderstood. Many saw it as simply an acceleration of the industrial cycle, when in fact it was a paradigm shift: don’t produce to test, but test before you produce.

Don’t fall in love with the solution, but be passionate about the need.

Selling a need VS selling a solution

Agile product management seeks to identify what can be validated with minimal effort and cost. This is where the creativity of growth hacking comes in, which has paved the way for ingenious approaches to assessing the appeal of a product even before it exists.

Dropbox is a prime example. In 2007, before writing a single line of code, Drew Houston posted a simple demo video. It showed a fictional prototype capable of syncing files with a single click. In reality, the product did not yet exist. Within days, tens of thousands of people had signed up for the waiting list. That signal was enough: the need was very real.

This strategy perfectly illustrates the difference between “putting the cart before the horse” and “checking that there is indeed a field to plow.” Agility is not about going faster, but about going more accurately—by building only what has proven to be necessary.

The priority here? Validate the need on a significant scale before validating the opportunity.

The prioritization chain

Prioritization approaches have often been misused. Tools such as MoSCoW, RICE, and Impact/Effort matrices have become ubiquitous, sometimes without a real understanding of the agile logic they were supposed to serve.

In a truly agile approach, priority is not decided solely on the basis of effort or supposed impact, but on what remains to be learned. Each test has its logical order:

- Need: Is there really a problem to be solved? And how can it be measured?

- Opportunity: Does this problem concern an identifiable market? Which segment is the most promising?

- Desirability: Is the proposed solution appealing? Does it move the need indicator?

- Usability: Is the solution compatible with the target customer or user and their context? Once tested in the field, is the solution actually adopted?

- Feasibility: Is the proposed solution achievable in the context, and are the costs and deadlines commensurate with the opportunity?

- Viability: Is the business model viable on the scale of the target market?

Too many entrepreneurs skip these steps. For fear of having their idea stolen, they keep quiet, build in secret, and then discover too late that they have developed a product that no one wants or that is not viable. This is the classic mistake of those who prioritize the solution over learning. Agility, on the other hand, proposes the opposite: learn first, build later. Test the need before testing the solution. Because the only thing you can really fail at in time is a hypothesis.

Prioritization based on customer and user experience

Added to this is a second key to understanding: differentiating the value of value drivers.

To illustrate this distinction, I often use the famous AARRR acquisition funnel, introduced by Dave McClure. This model breaks down the user journey into five stages:

- Acquisition: How users discover the product.

- Activation: Their first positive experience.

- Retention: Their desire to return naturally.

- Revenue: The economic value generated. In the context of this prioritization, I avoid this axis because, for me, it plays out in parallel with the rest. So we’re more on the AARR side.

- Referral: Word of mouth, a sign of perceived value.

With a view to immediate implementation, teams often focus on the first two stages, acquisition and revenue, because they are visible and reassuring. We want to present a product, make it known, generate traffic, and sign contracts. But an agile approach puts the question back in the right order: before trying to sell, we need to make sure there is value to be delivered.

Retention is a reflection of real value: if users come back on their own, it’s because the product offers them something concrete, repeatable, and useful. Take the example of a sleep tracking app. If it invests heavily in advertising before proving that it really helps its users sleep better, it may generate downloads, but not sustainable usage. Every dollar spent on promoting it then becomes a dollar thrown out the window. Thus, promoting a product that offers nothing is accelerating its demise. Impact factories reverse this logic: they first work on perceived and experienced value—the kind that naturally creates retention—before deploying distribution channels. Adoption is then no longer a conquest, but a consequence. Prioritization is then done in the following order:

- Retention

- Activation

- Referral and Acquisition in parallel

Prioritize the survey before implementation

But here again, there is a pitfall in implementation: we believe that value can only be created through the product itself.

However, modern marketing has profoundly changed this view. It is no longer limited to promoting a solution: it also serves to gauge demand, sometimes long before a product even exists.

This is known as exploratory marketing. Rather than building an expensive prototype, a series of articles, videos, or targeted advertisements can be published to test interest in a topic. By measuring click-through rates, waitlist sign-ups, or interactions on a landing page, initial validation of the need and the population actually concerned can be obtained.

Many startups do this: before coding any features, they test several advertising messages linking to different pages. The page that attracts the most sign-ups often reveals the problem perceived as the most painful—and therefore the best opportunity to explore.

In other words, marketing is no longer just a value amplifier, it is a potential value detector. It allows you to learn before you act, and then invest where the signals are strongest.

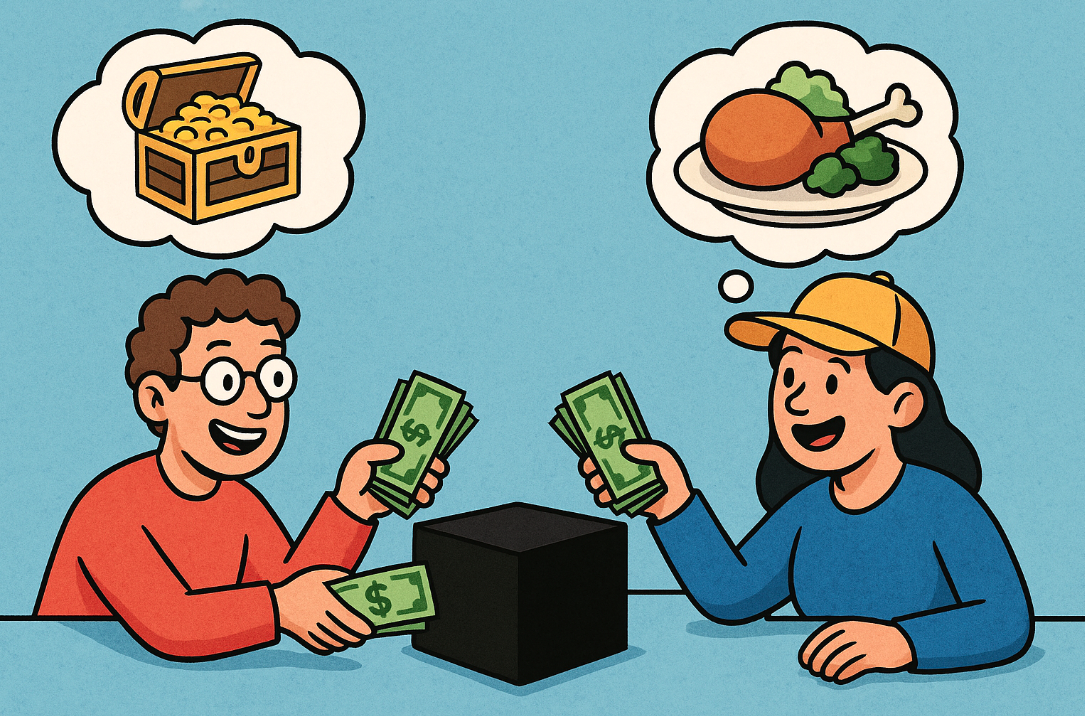

Faking it before making it

Finally, the modern approach to design adds an essential building block to the process: embodied experimentation.

Methods such as Design Sprint, popularized by Google Ventures, make it possible to simulate in a few days what the user experience of a product would be like before it even exists. The goal is not to “design quickly,” but to make an idea visible so that it can be tested quickly.

In the same vein, the principle of “fake it until you make it” does not mean “deceiving,” but rather “manually testing what will later be automated.” Instead of coding a complex platform, its mechanisms are reproduced by hand to see if it delivers on its promise.

This is exactly what Airbnb did in its early days: the founders took photos of the apartments themselves and managed exchanges between hosts and travelers to verify that the model worked before developing it.

Conversely, many entrepreneurs launch community apps or marketplaces without ever having moderated a community or orchestrated real exchanges. They build a tool before understanding the social dynamics it needs to support. The result is predictable: a beautiful interface, but no use.

Modern design, when properly understood, reminds us of a simple truth: before creating an experience, you have to test it.

The agile product manager becomes a priority orchestrator

From this point on, the role of the Product Manager takes on a whole new dimension.

They become a learning strategist, at the crossroads of marketing, design, and technology. Their goal is no longer just to manage the delivery of a product, but to orchestrate a progressive understanding of what it should be.

In this logic, their backlog does not contain features, but hypotheses to be tested: needs to be validated, messages to be confronted, uses to be observed. Each test becomes a building block of knowledge that feeds into the vision for the product.

Sometimes this means putting development on hold, even temporarily—not to slow down, but to ensure that the team is moving in the right direction. A seasoned Product Manager knows when to say, “Stop, we haven’t learned enough yet.”

In this sense, the product is no longer just an application or a deliverable: it is a living system of experiences, feedback, and adjustments.

This is why we can no longer consider the old definition of a product as simply a good or a service.

Continued here: What is a product?

Author of Impact Factories / Co-founder of Shy Robotics and Product Whys / Head of Product at Dassault Systèmes / Engineer passionate about innovation and entrepreneurship

Full bibliography here