The networking event is held at NUMA, a vibrant coworking space in the heart of Paris, lit by atmospheric LED fairy lights and screens showing futuristic demos. As soon as she crosses the threshold, Sophie is overcome by a mixture of excitement and stage fright. Two hosts hand them stickers: first names to write on, then little flags to indicate the languages they speak—cosmopolitanism obliges. To Sophie’s surprise, Esperanto is even among the options.

She and Julien comply; Julien can’t resist the urge to draw a tiny melon next to his name. With the stickers in place on their chests, Sophie meets his gaze and whispers, “Ready to socialize?” half-challenging, half-encouraging. “As ready as we can be,” replies Julien, scanning the room. They then walk away, each toward a different group, drawn in by the multilingual hubbub and the promise of new ideas.

Circulating among the entrepreneurs, Sophie approaches those present with curiosity and enthusiasm. “What exciting project brings you here tonight?” she asks to open the door to conversation. With each answer, she listens attentively and follows up with increasingly pointed questions: “How did you overcome your initial challenges?” or “What strategies are you considering to grow?”

Sophie moves from conversation to conversation, listening to stories of start-ups, pending resignations, and doubts whispered over drinks. Some are still at the PowerPoint stage, hidden in a desk drawer. Others have already raised funds and survived a pivot or two. Little by little, her vision of entrepreneurship becomes more nuanced, and her own uncertainties lose their gravity.

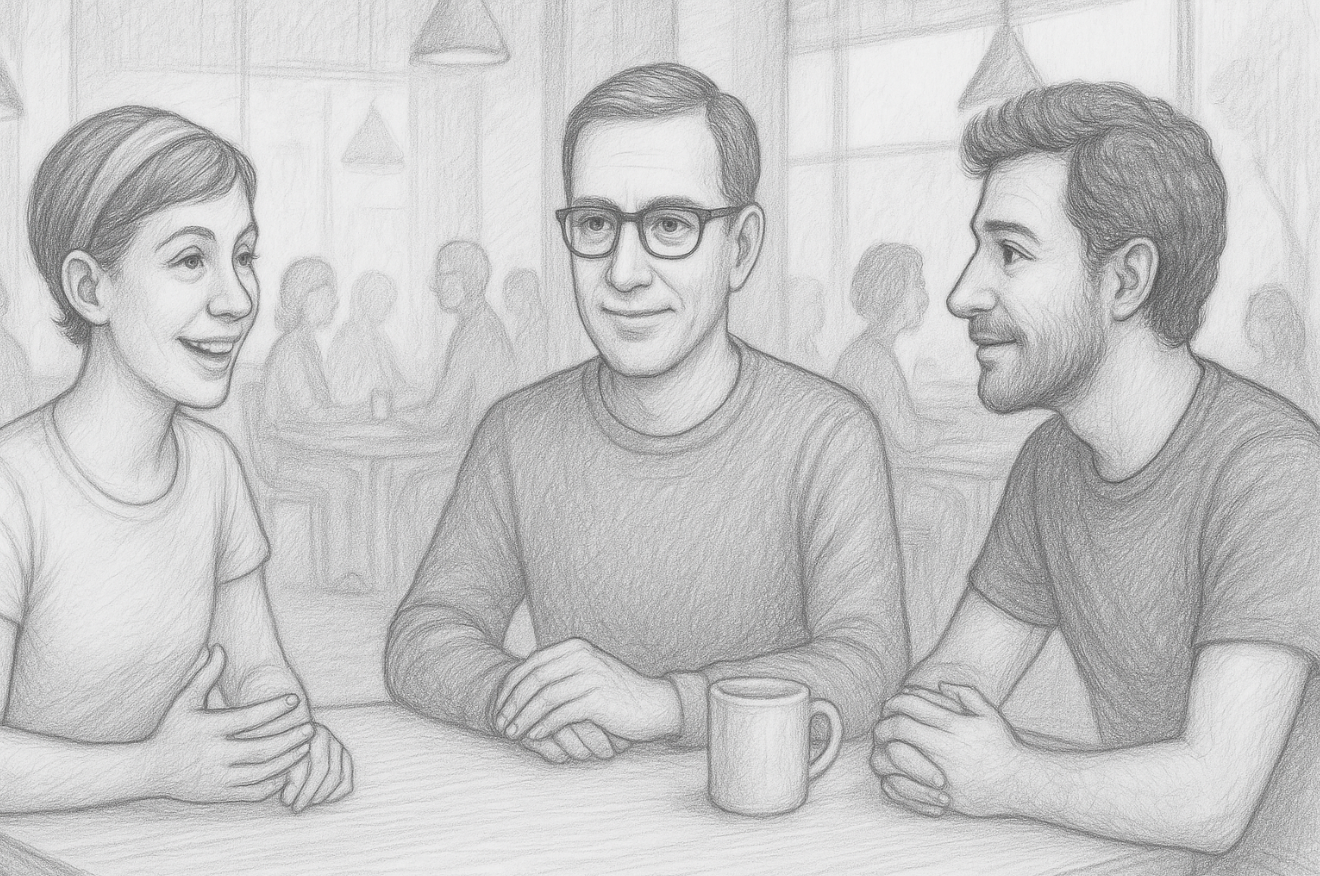

As she approaches a table set back a little, occupied by a small group laughing softly, she notices Max. He is there, calm, cup in hand, smiling quietly, looking attentive. She doesn’t know him yet, but he exudes a rare presence, the kind of person you feel you’ve met before, who inspires confidence just by looking at him. The group disperses, leaving only him behind.

She hesitates for a second, then steps forward. “Hi, I’m Sophie. I’m working on a project called MelonsNet.” He nods slightly. “Interesting. Tell me more!”

She continues, summarizing in a few sentences their idea for a mind-reading headset, the beginnings, the ambitions. He listens without interrupting… until he does. “Tell me, Sophie, what need are you really trying to fill?”

The question is blunt, with the disarming simplicity of those that require a moment’s thought. Sophie realizes that she has never thought about this in detail. Although taken aback, she recovers and begins to describe their technology with obvious pride. “So, our mind-reading headset is based on cutting-edge sensors, inspired by Stephen Wolpaw’s research on brain-machine interfaces. These sensors capture brain waves and translate them into electrical impulses, a bit like an EEG but more complex,” she explains. “Then we developed a machine learning interface that interprets these raw signals. To do this, we rely on deep neural network algorithms, such as those explored by Yoshua Bengio, to refine predictions in real time.”

Max’s silence unsettles Sophie slightly, but she continues, carried away by her passion. Her eyes shine, animated by the desire to convince.

“Our filter system,” she explains, “is inspired by Marvin Minsky’s work on emotion recognition. In short, we don’t transmit all thoughts, but only certain categories: emotions, intentions… That’s what makes our headset unique. We don’t just read electrical impulses. We interpret mental patterns, thought structures. We capture the essence of what the user wants to say, the moment they think it.”

Max listens, still wearing the same warm smile, but without revealing a single thought. When she finishes, silence falls. It lasts. A long time. Too long. Sophie remains frozen, tense as a string waiting for a verdict.

Then, calmly, almost gently, Max speaks: “That’s impressive, really. And we can tell you know your stuff.” He pauses. “But… what need are you trying to fulfill?”

Sophie is taken aback for a moment, then takes a different approach. “Well, our headset breaks down barriers between people, improves mutual understanding, reduces conflict… Ultimately, it contributes to humanity.”

Max tilts his head slightly, as if trying to see the project from another angle. “I see,” he murmurs. “But have you identified any concrete use cases?”

Sophie nods vigorously. “Of course! In meetings, for example, it could facilitate understanding between participants. And imagine diplomatic negotiations, where every nuance counts… The possibilities are endless.”

But Max’s expression remains impassive. He allows a brief silence to pass, more uncomfortable than the previous ones, then continues, more directly: “Are diplomats or meeting facilitators already using your headset?”

Sophie lowers her eyes slightly. “No… not yet. The headset isn’t advanced enough for that.”

Max doesn’t let up, but his tone remains calm. “And have you talked to them? To find out if they would be interested, even in theory?”

She looks down again, her voice less confident. “No… without a prototype, they wouldn’t see the point…”

Max observes her face for a moment, attentive to the slightest inflection. Then, without raising his voice, he asks the question that hangs in the air: “So how do you know that your headset will really meet those needs?”

Sophie falls silent, sensing the subtlety of the question. For the first time, she realizes that, despite the technical possibilities, the definition of specific needs may lack solidity.

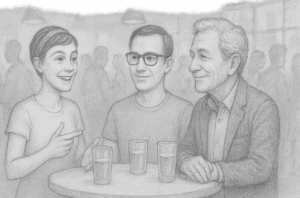

Julien, who had been listening to the conversation a few steps away, approaches discreetly. Sophie takes the opportunity to make the official introductions, and Max congratulates the duo on the impressive progress of their project. But suddenly, he glances at his watch, jumps slightly, and then apologizes for his hasty departure. He hands each of them a card, scribbles an email address on the back, and looks them each in the eye.

“Promise me you’ll stop by the incubator. I can really help you get through this crucial stage,” he says with a sincere smile, tinged with contagious energy. Then he disappears into the hustle and bustle of the evening, leaving behind a mixture of enthusiasm, doubts… and a strange feeling of a missed opportunity.

Julien and Sophie, inspired by their encounters but a little tired, decide to head home too. As they leave NUMA, they promise to debrief each other the next day at the office about their discoveries and ideas for moving forward with fundraising. On her way home, Sophie takes a few moments to call her sister, who is looking after her son, promising to spend time with him next weekend and take him to the zoo.

The next day, Sophie and Julien meet up with the MelonsNet team at the office for another day of work. As he does every morning, Julien starts with the fifteen-minute team ritual where everyone recaps the day’s objectives and any sticking points that require help or the postponement of certain deadlines. Sophie and Julien discuss their meeting with Max the day before and plan to decide on the next steps within an hour of the team meeting. The developers take the opportunity to share that they need to recalibrate the mind-reading headset because they have discovered a disturbing problem: when someone gets too close, the headset confuses the wearer’s information with that of the person passing by.

After the session, Julien and Sophie retreat to a meeting room to discuss their meetings the day before. Sophie breaks the silence by leaning toward Julien. “Max really threw me off with his questions about use cases,” she confides. “I understand that he wants concrete examples, but he kept coming back to it as if it were the only thing that mattered. We’re revolutionizing the world by creating a technology that will give rise to new needs, just like smartphones and humanoids did in the past, and they’re asking us to talk to users who won’t be able to visualize our technology. He’s a little off the mark…”

Julien shrugged, annoyed. “I totally agree! Frankly, I don’t get it. What’s the point of focusing so much on use cases if our product isn’t even ready? It’s a bit silly, isn’t it? We’re still finalizing the headset, and he already wants concrete proof of use. He doesn’t understand what we’re doing… “

Sophie looks at him, a glimmer of hesitation in her eyes. “At the same time, he works with startups… and we know we’ve missed something. Maybe we’re missing an anchor, something solid to structure our development.”

Julien shakes his head skeptically. “There are also a lot of dream sellers in incubators. Look at all these public programs that boast about the number of startups they support, but never about the jobs created or the real impact. Their pitches are always about financiers, institutional partners… never about customers or real results. They specialize in raising public funds at the expense of our taxes.”

He pauses, then adds in a more serious tone: “And often, they recruit former entrepreneurs who have failed and are still looking for the magic formula. So they test methods on the newcomers, banking on their naive energy. Before we rush in, let’s take the time to dig a little deeper into Max’s incubator. Are you up for it?”

Sophie nods slowly, thoughtfully. “You remind me of an American friend,” she says. “He used to gently mock our French incubators. According to him, while theirs, like YC, are run by successful entrepreneurs, ours hire those who have failed. He found it almost reassuring, he added with a smile, because it meant we weren’t really likely to compete with them.”

Julien smiled, but she continued, more seriously: “He also said that in the United States, large companies buy up startups as soon as their value skyrockets. Here, we wait for them to crash and burn so we can buy them up at a low price. He had heard about Bernard Tapis and was impressed that someone had been able to ride this cultural wave to success in entrepreneurship. He concluded by comparing it to a prestigious engineering school that selects its candidates by starting with the least talented.”

A silence follows, heavy with realization. As if to reassure himself, Julien adds, “Americans are so arrogant. We’re not that bad in France… And I’m sure they do the same thing. He only looked at the biggest players with plenty of resources to reach that conclusion.” Then, the two of them set about their research: press articles, testimonials from former incubatees, support histories. Quickly, the facts speak for themselves. The Vonaroga incubator, run by Max, has a remarkable success rate. Iconic startups have emerged from it, some of which are now world-renowned.

Julien put down his tablet, deep in thought. “We can’t stay in this state of confusion.”

Sophie looks up and stares at Julien. The decision is made: they will contact Max again. After a few minutes on the phone, he arranges to meet them in the café of the hospital where he is currently staying.

Julien frowns. “A hospital? What kind of meeting is this?”

An hour later, they meet at the location, their minds racing, eager to finally understand why Max is so insistent on the subject of use cases. Sitting in the café, surrounded by the bustling atmosphere of the hospital, they explain their problem to Max. “We must have missed something when we met. We didn’t understand how you imagine validating a use case if the headset isn’t functional,” Julien admits.

Max listens to them in silence, attentive, his hands folded in front of him. Then, with a reassuring smile, he speaks in a calm voice. “You’re going through a complex phase, but it’s a classic one for creators of innovative startups.”

He pauses, looks at them in turn, then continues. “There are several types of founders. Some start with promising technology but are still feeling their way commercially. Others have a clear idea of the market, a business vision, and are looking for the technology that could make it a reality. Some identify a need—more or less clearly defined—and try to solve it. And then there are those who have neither technology nor a specific need, but who have incredible energy, a ability to bring people together and adapt, banking on finding an opportunity at the right time.”

He looks at them kindly. “In your case, the technology is there. What you’re missing is a clear, tangible, urgent need. A problem that really deserves to be solved.”

Sophie and Julien nod thoughtfully. Julien finally says, “We’re pretty visual… Could you draw us a diagram to illustrate that?”

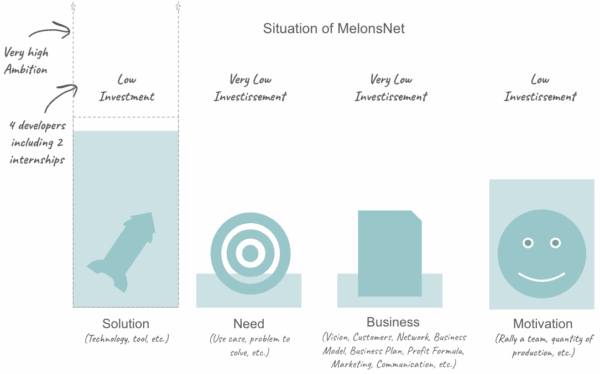

Max smiles, grabs a marker, and walks over to the whiteboard hanging on the wall. He draws four columns: Solution, Need, Business, Motivation. “These are the four pillars on which most projects are structured. Every startup starts with one or two of these strong areas.”

He writes MelonsNet in the Solution column, then underlines Motivation with a heavy stroke. “Your technological solution is ambitious, and the team’s energy is obvious. But the other two columns—need and business—are almost empty.”

Julien crosses his arms, deep in thought. Sophie remains focused. Max continues, without beating around the bush. “There are two main types of startups. Those that survive thanks to their customers from the outset, known as bootstrappers. And those that require heavy investment—often to finance R&D or because they are aiming for a low-margin mass market model. MelonsNet, you’ve positioned it as a deep tech startup, but if we look at it objectively, even your strong point, R&D, is under-resourced. Two full-time developers, two rotating interns… that’s very thin.”

He turns to them. “You were lucky to find brilliant interns who were available outside of the academic calendar. But that won’t be enough.”

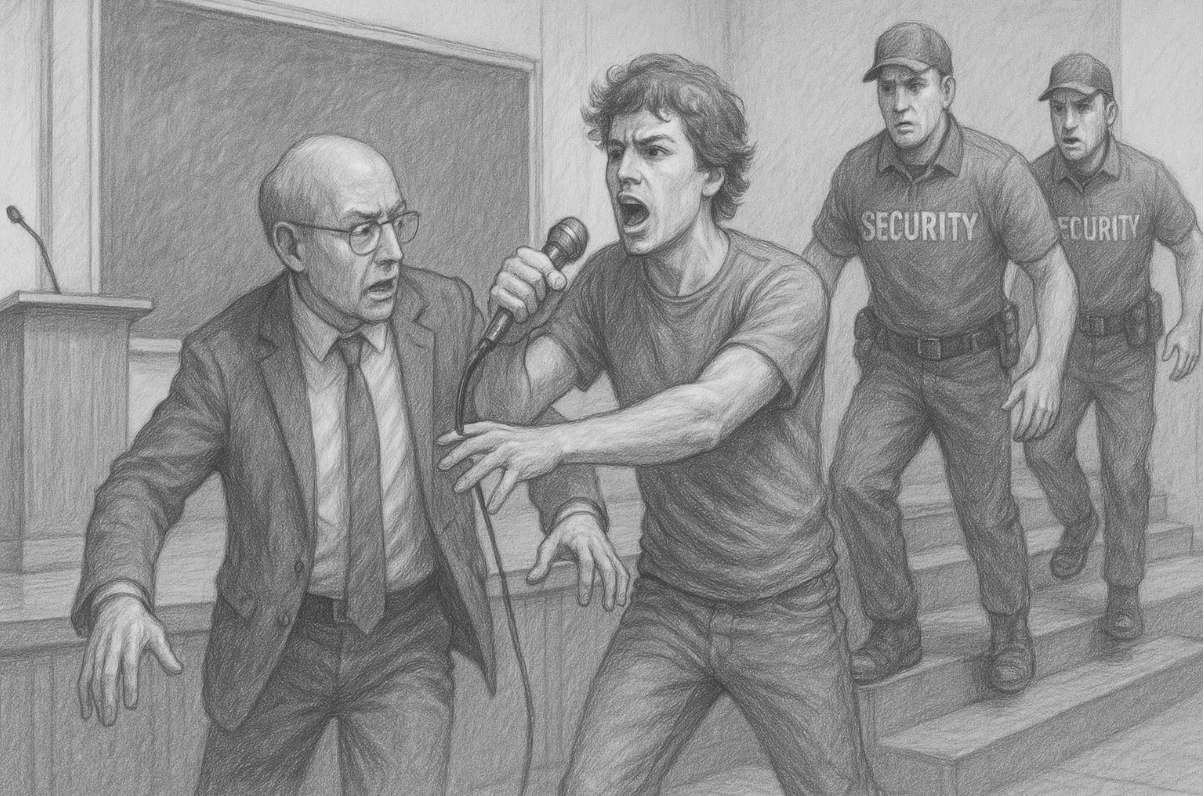

The silence that follows is thick, almost palpable. Julien keeps his arms crossed, his gaze sombre. He finally breaks the silence. “I understand your point of view, Max, but that doesn’t solve the real problem: how do you expect to attract users if the headset isn’t even finished?”

Max remains unperturbed. “Julien, it’s not about selling it or getting people to use it now.”

Julien raises an eyebrow, stung. “I never mentioned selling it.”

Max tilted his head slightly. “You mentioned interest in a finished headset. We’re not far off. But that’s not the point. It’s not about coming up with a product before looking for users. It’s about investigation. Exploration before developing anything. How can you know what your future users expect—in terms of features, performance, ergonomics—if you haven’t identified a concrete use case? It’s not the product that should guide your decisions, but the information gathered in the field. That’s what charts the course. That’s what sets the course and gives meaning to deadlines.”

His tone becomes more engaging. “And to address your concern, it is entirely possible to sell a product that doesn’t yet exist, as long as you present a clear vision and inspire confidence. Take the example of the Airbus A380. When they proposed this aircraft to airlines, it was nothing more than a project on paper. No working model, no prototype, just simulations, financial models, and an ambitious vision. And yet, they managed to convince several companies to sign firm orders.”

Seeing Julien’s interest grow, Max adds more details. “The Airbus teams first identified the needs of airlines, such as transporting more passengers over longer distances while reducing the cost per seat. Then they presented how the A380 would meet these expectations thanks to its unprecedented size and energy efficiency. They even used economic models to prove that the long-term operating costs would more than offset the initial investment. They weren’t selling an airplane, Julien, they were selling a solution to real problems.”

Max approaches, his gaze intense. “What I’m saying is that you can do the same thing. If you fully understand the real needs of your users, you will not only be able to guide your development, but also begin to build a relationship of trust with your future customers, even if the product is not yet finished.”

Julien and Sophie, now convinced by the approach, exchange a knowing glance before Julien turns to Max. “Okay, we see where you’re coming from,” he begins. “But in practical terms, where do we start to launch this investigation?”

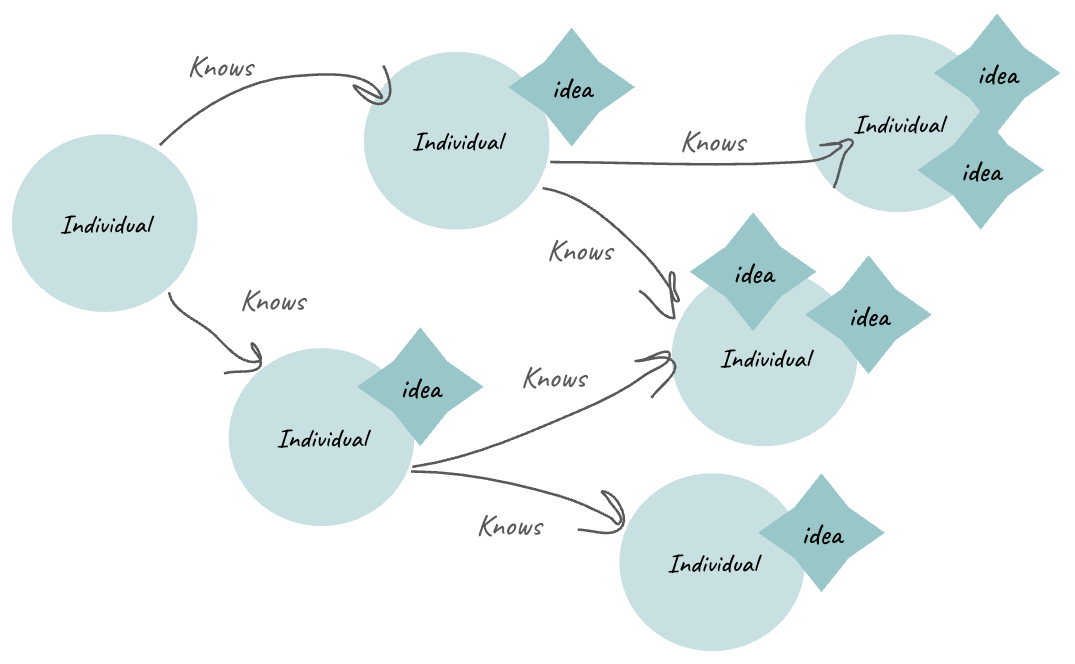

Max, pleased with their progress, replies. “To identify a need, you have to meet people. Not necessarily those who have that need directly at the outset, but at least people who can give you leads or point you in the direction of the right people to talk to.”

Max then stands up and introduces Leo, who has just walked through the door of the café. “I asked him to come by because he has already launched several innovative companies in the incubator where I work. When I told him about you earlier, he said he happened to be in the area.”

Leo approaches, smiling, and shakes hands with Julien and Sophie. “Hi, I heard you needed some advice to save your business. I’d be happy to help.”

Stories from entrepreneurs and product managers

To step back from the content of this first chapter, I would like to share a series of inspiring testimonials.

🎥 Watch the videos

Lydian Feneck (in French), founder of Gamearly, explains how neglecting a community-driven approach can lead to missing a product’s true value.

Sébastien Tricoire (in French), CTO of Cezigue, explains how incubators unite communities to maximize entrepreneurs’ chances of success.

Anil Narassiguin and Pierre Vidal (in French), co-founders of FlyRenov, explain how personal challenges can become an opportunity to build a network.

Bertrand Lafforgue (in French), CEO of Konverso, explains the importance of personal networks in achieving success.

Paul Benoit (in French), CEO of Qarnot Computing, explains the organic approach to building a network around a project.

Christophe Remillet (in French), co-founder of OneVisage, explains how professional experience can serve as a driver for network growth.

Lara Gervaise (in French), co-founder of Virtuosis AI, builds her network through continuous experimentation around her product.

Author of Impact Factories / Co-founder of Shy Robotics and Product Whys / Head of Product at Dassault Systèmes / Engineer passionate about innovation and entrepreneurship

Full bibliography here