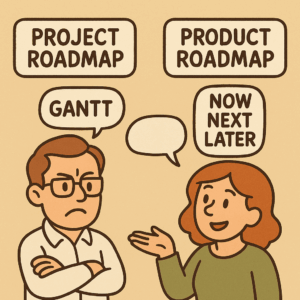

The roadmap is one of the most common areas of friction between teams working in agile mode and those operating in a V-model cycle. This is hardly surprising: the former seek to carry out a series of tests to mitigate risks for the future, while the latter have already finalized all the decisions to be implemented, sometimes over a period of several months.

But where does this difference really come from?

Rather than theorizing right away, let’s start with a scene that every product manager has experienced. It’s a simple, concrete, almost mundane situation… and one that reveals, better than any diagram, what kind of roadmap we’re really talking about.

It’s 9 a.m. at NovaMove, an SME specializing in professional removals.

For the past year, the company has been trying to digitize its customer experience by launching an app: quote tracking, preparation, checklist, notifications. In the meeting room, an urgent problem is occupying everyone’s attention: customers are complaining that they don’t understand where their move is at. A simple but explosive irritant.

Marc, the operations manager, opens the meeting: “We’re receiving twelve complaints a day. People never know if the team will arrive on time, if the volume has been validated, or if the invoice is correct. It costs us time and damages our NPS. We need to fix this as soon as possible.“

Sofia looks up from her computer: ”That’s exactly what we’re seeing in the app too.

Users log in but don’t come back. They don’t have enough information during critical days.“

This time, everyone is talking about the same problem: customer information is not transparent enough.

Two approaches, one irritant

Marc projects his Gantt chart: ”To solve this problem, we can accelerate the ‘Web Customer Portal’ project. We’ve planned it out: analysis this month, design in July, development in August, testing in September, go-live in October. It’s a classic project: a few screens, some workflow, internal integration.“

He calmly explains: ”The main risk for us is not sticking to the schedule.

The sales team has been waiting for this portal for a year. We can’t spread ourselves too thin.“

Sofia speaks up, clearly disagreeing: ”I understand, but what you’re proposing will take too long. We don’t even know if a complete portal will really solve this specific problem. Maybe customers just want a simple notification: ‘Your team will arrive in 30 minutes.’” “

Marc frowns: ”We can’t send that kind of notification without checking the logistics behind it. It could become an operational nightmare if it’s not reliable.“

Project vs. Product: Two Opposing Risks

Lea slowly raises her hand, her tone calm but firm, as if to bring everyone back to the same point. ”Wait. You don’t disagree… you’re just not talking about the same risk. And it’s normal that your roadmaps don’t look the same.“

She moves closer to the screen displaying Marc’s Gantt chart and points to the blue blocks that follow one after the other. ”Marc, you’re managing a project risk. What scares you is very clear:

— misjudging the effort required,

— delivering late,

— burning out the teams along the way.“

She turns to him, almost conspiratorially: ”In your context, your Gantt chart makes sense. You’re in control of the scope, you know the business, and the ‘Web Customer Portal’… that’s exactly the kind of thing you’ve been experts in for years. “

Lea now turns to Sofia, who stands with her arms crossed but a determined look on her face.

”For you, Sofia, the risk is not the same. You carry a product risk. What worries you is something else:

— building a portal that no one will really use,

— missing the real expectations of customers,

— investing weeks in a gamble that doesn’t solve the problem.“

She softens her voice: ”Your goal isn’t to deliver for the sake of delivering. It’s to understand what really improves the customer experience… and you can only find that out by testing.”

Lea takes a step back to look at the whole team. “You’re dealing with the same irritant, the same issue… but not with the same uncertainty. And that’s exactly why your approaches differ.”

The agile roadmap

Sofia turns her screen back on and projects her roadmap. Three simple columns: Now, Next, Later. Nothing complicated, just the essentials.

“For me, we start simple. NOW:

— we prototype an SMS notification “Your team is on the way,”

— we send it to about thirty customers this week,

— and we immediately measure the impact: fewer calls? Fewer complaints? More clarity?“

She moves on to the next column.

”NEXT:

— if it works, we integrate it cleanly into the app,

— if it doesn’t work, we change tack: maybe a timeline in the app, or an automatic message after volume validation. We explore.“

Finally, she points to the last column.

”LATER:

— the complete portal… if the tests show that it’s really necessary.”

A silence falls. Marc rubs his chin, surprised. “Wait… are you telling me that before launching a €150,000 portal, you want to check if a simple notification can solve 60% of the problem?”

Sofia nods. “Exactly. If that’s enough, we save time, money, and immediately reduce customer frustration. And we avoid three months of unnecessary development. “

Marc lets out a half-chuckle, a little disarmed. ”What if your test fails completely?“

”Then we’ll have learned quickly,“ Sofia replies without hesitation. ”A few days of work, not three months. And we’ll reorient. Maybe your portal will be the right solution, maybe not. But this time, we’ll know… instead of just believing it. ”

Analysis

The scene between Marc, Sofia, and Lea perfectly illustrates the root cause of the tensions surrounding the roadmap. At first glance, they were talking about the same problem—customers not receiving enough information during their move—but their approaches to solving it were completely different. The reason for this is not the personalities of the individuals involved, but the nature of the risk that each of them manages and, by extension, the operational model to which they belong.

When Marc defends his Gantt chart, he is not just talking about a tool: he is explaining how the project mode works, inherited from years of practice in a stable and mastered profession.

For him, as for any organization that has been repeating a familiar process for twenty years, the key decisions have already been made: the scope is clear, the steps are defined, and the risks have been identified. Under these conditions, it makes sense to plan everything over a long period of time with:

- a scope set from the outset,

- a sequence of linear steps,

- and a predefined allocation of resources.

The V-cycle—or project mode—works very well when there is little uncertainty, as is the case with the moves that NovaMove has been managing for two decades. The company knows how to estimate volume, plan a team, calibrate a quote, and anticipate contingencies.

In this context, derisking does not need to be systematic: it has already been done over the years.

Conversely, Sofia’s reaction highlighted a different logic: that of product mode, specific to environments where the solution is not known in advance.

NovaMove’s mobile app is not a long-standing service: it is a growth driver that is still experimental and subject to unpredictable user behavior. Here, the risk is not missing a deadline: it is building something that is useless, poorly targeted, or too costly for the actual impact.

Sofia thinks in terms of:

- hypotheses,

- tests,

- weak signals,

- learning,

- and business impact.

Her role is not to execute a fixed roadmap, but to reduce uncertainty about what really creates value for the customer. This explains why her “Now/Next/Later” format is deliberately flexible: it projects problems to be solved, not fixed solutions.

Differences in team structures

The scene also shows that the roadmap is not a neutral tool: it reflects the very structure of the organization.

- The project mode works with temporary teams, set up to deliver a defined scope and then disbanded. Their performance is measured by their ability to deliver the planned features within the planned timeframe.

- The product mode, on the other hand, relies on permanent teams assigned to a functional scope or user segment. They exist as long as the product or their functional scope exists. Their performance is measured by the impact they generate: retention, satisfaction, engagement, revenue, etc.

The scene concludes with an obvious point that the discussion has made tangible:

Project and product roadmaps cannot be built in the same way.

- A project roadmap anticipates: it is based on certainty, sequence, and coordination.

- A product roadmap explores: it is based on learning, adaptation, and reducing uncertainty.

This is why a project can be planned over three years, with a set of predefined features, while a product is expressed more in terms of:

- business objectives to be achieved,

- hypotheses to be tested,

- and a dynamic format such as Now/Next/Later that accepts, or even seeks, change.

A scam?

Some might respond, “Your approach works with five developers in a young startup, but not for orchestrating ten interconnected teams.” And in a way, they would be right: I have deliberately simplified things. As soon as we scale up, the issue is no longer just the form of the roadmap, but the governance of dependencies, the management of external constraints, capacity ranges, and cross-functional commitments.

In these contexts, a Gantt chart remains useful: it visualizes sequencing, critical paths, and collision risks. But it does not create adaptability. This comes from other mechanisms: common cadences (PI Planning, Scrum of Scrums), prioritization (WSJF, cost of delay), shared objectives (OKR), and product ops to structure practices between teams. It is these organizational artifacts—not the tool—that allow the plan to be adjusted when reality changes.

The Now / Next / Later model plays a different role: it is a representation by horizons. It simplifies communication, explicitly exposes uncertainty, and avoids false promises. Some teams use it as a daily support, others as a directional synchronization tool, but it is not enough on its own to manage heavy dependencies or regulatory constraints.

The real difficulty when working with multiple teams comes from the types of dependencies:

- technical (one module must be ready before another),

- organizational (different teams, divergent priorities),

- capacity (same experts on multiple topics),

- external (partners, regulators, suppliers). It is their orchestration that determines predictability as much as agility—even more so than the format of the roadmap. This topic deserves an entire article of its own.

But all that will be the subject of another article…

Author of Impact Factories / Co-founder of Shy Robotics and Product Whys / Head of Product at Dassault Systèmes / Engineer passionate about innovation and entrepreneurship

Full bibliography here